Interviewee: Norah Mitchell, born Cahill (CAH-hill), Dec. 12, 1931, Guildford, Surrey, England. Died May 2016, Floyd, VA, USA.

Father: Joseph Robert Cahill. Mother: Florence Ellen (Smith)

Interview: conducted December 26, 2014, in Floyd, Virginia

Interviewer and editor: Randall A. Wells, b. 1942. Retired Professor of English & Speech, Coastal Carolina University. Former Director of the Horry County (SC) Oral History Project

Italicized parts added by Norah to indicate memories evoked by reading the original interview.

I was raised in London. My earliest memories— my father would bring piecework home and the children and my mother would sit around the table threading nuts and bolts and screws, and we would do it together [illustrates with stretched-out arms]. Another: going to a Shirley Temple movie. Strangely enough, I can remember the address: 16 Bayham St., Camden Town, London [a borough that forms part of Inner London]. Maybe I can remember because my family was together. I had one brother and a sister at that time.

In September, 1939, England was preparing for war. I remember barrage balloons—great silvery, gas-filled balloons that they would float up to keep aircraft from coming down. [Sometimes called “blimps,” they were tethered with metal cables.] Also there were searchlights that would come on for practice [motions]. The lights would sweep across the sky and also bounce off the balloons. One night my mother sent me down to the bakery to get a loaf of bread, and it was after dark, I will always remember it was Hovis brown bread. When I was going, it was the first time that they had decided to test the air raid sirens. I had no idea what it was. I screamed and screamed and ran home terrified and my Mum explained what was happening.

I guess I lived the normal life of a child, went to Catholic school, where the nuns slapped me on the left hand for writing with it. I remember my Dad called me “Olive Oyl” because I was tall and skinny like Popeye’s wife. I adored my daddy and I think I was probably his favorite. (At least I felt like I was).

The next thing I remember: my mother taking us to Paddington Station [in Central London]. By this time my second brother, Tony, had been born, in February, 1939. The British government had made plans a few years earlier, as the war seemed inevitable, that all the children should be evacuated from London to a safe place so, in September 1939, my sister Tess, brother Bob and I were to be evacuated; Tony was only six months old and stayed with Mum. I clearly remember the railway station and hundreds of scared and crying children. We all had a tag around our neck with a big label (with our names) and we all had our little gas masks. They were all in a little cardboard box, and we held it on a string around our necks. Everyone had been issued a gas mask in England. There was my brother Bob… I think he was six, I was seven—and sister Theresa was four. I guess it was kind of chaotic—parents giving their children to caretakers to put them on a long, long train. The very last thing my mother said to me was, “I want you to promise that you will take care of your brother and sister all the time you’re gone.” And that was what I did.

The train was like fourteen coaches long, filled with children and chaperones. We were going to a place in Cornwall–St. Austell, near St. Austell Bay. [This bay is in the English Channel and Cornwall is a county in far southwest England.] I was told soon after we got off the train that German fighter planes had followed it thinking it was a troop train. Fortunately the station at St.Austell was covered so the disembarkation was not seen from the sky. When all the children got off, the train was pulled onto a siding, where it was strafed [i.e., raked by machine-gun fire at close range].

We were taken to a big church or school and the foster parents were all supposed to come and pick out their children. They picked out the child they wanted, and Bob got picked right away. He stayed there for the whole war, four-and-a-half years. I was one of the leftovers—I was skinny—nobody wanted me. At the very end they put us into cars and went around knocking on doors asking if they would take in children. My sister and I were taken in by a nice couple. We thought they were old (although they weren’t), and my sister was terrified by old people. Saturday night was bath night and I remember a big boiler in the kitchen, where the water was heated and a big galvanized bathtub in front of the kitchen fire. The hottest water was for the first bathers, my sister and I, and Tess screamed at the temperature.

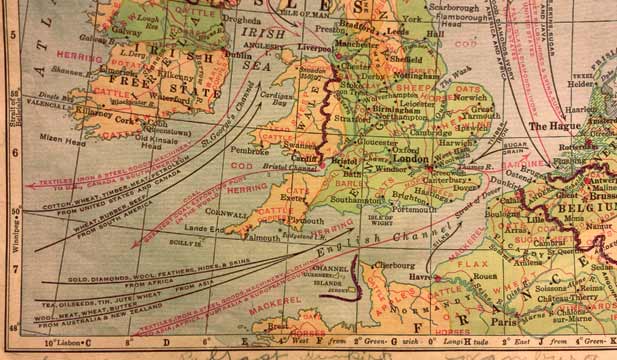

The nice people we lived with had a little cupboard under the stairs that was directly across from the front door. There was a mattress and blankets in the cupboard and we would go there when the air-raid sirens went off. I don’t think we were in any direct danger because the Germans would fly over us to bomb Falmouth, which was a big Naval base, fairly close by. Anyway, they would fly right over the house. Fred would stick his head out the door to watch the planes, and his wife would tell him to come in, and he would reply, “If one of those bombs has my name on it, it’s gonna get me whether I’m inside or out.” [Please see map. It names Falmouth on the English Channel near the southwestern tip of England, shows the distance between Cornwall and London, and locates Cornwall in relationship to the German-occupied coast of Europe.]

Wallace W. Atwood. New Geography, Book Two. Boston: Ginn and Co., 1941, 1943. Frye-Atwood Geographical Series.

Map by Rand McNally & Company. Courtesy Mike Vasaune.

Then my sister went to another place and stayed there the rest of the war. The people’s name was Parsons. My job was to watch out over my brother and sister, so I would check up on them all the time. I don’t know why I did this [action] one time—I’d lost touch with my sister and tracked her to her school, where I sat in the back of her class till I was found out.

I was sent to a couple of other places, don’t remember much. At one point I was sick and had to be looked after by somebody—some kind of sanatorium. One child in one of the places I lived died of diphtheria. Seems that they blamed me for it and sent me away to another house. It was located in Charlestown, which is a little fishing village on St. Austell Bay. [See Wikipedia, “Charlestown, Cornwall.”] It had a little harbor, which was covered over so mine-sweepers could be refitted. The men working on these boats had to have lodging, so would stay locally. The people I was sent to live with had taken in two lodgers and two other children, who seemed to be well taken care of, probably via money sent. At this point, I should mention that the government paid these “caregivers” a monthly allowance and also gave them our ration books.

The homeowners I will call Mr. and Mrs. Smythe. His first name I will call Cedric, but I don’t remember hers. I did not hear from my mother in four-and-a-half years; if she ever wrote or sent anything I was never told, so I began to believe I would never see her or my daddy again and would spend the rest of my life in that place. That was one of the things that she held over my head. “Your mother is dead, so you might as well do what I say.” I once said something about my mother: “Your mother’s dead. Stop your sniveling.” I was standing up ironing. Couldn’t stop, so she came over and slapped me. I just continued to work. I think I was probably ten by this time, but I don’t remember.

I was the household slave. I scrubbed floors, did the ironing, I remember there was a big iron pot outside the kitchen door where we threw all the leftovers and to this was added some kind of meal. One of my jobs was to mix it all together because it was slops (food) for the pigs. I also remember that there was a neighborly get-together for the slaughter of one of those pigs and everyone cleaned and hung up entrails, etc., to make sausage with. Everyone got to share the end results of the dead pig. In those days it was a blessing because there was very little meat to be had at the butcher’s shop. I remember standing in line for horse meat and even whale meat.

The Smythes had a little farm which was probably about a mile from the house. I used to walk there before school. My job was to take the goats out and tether them. There was a billy goat that scared me to death. After I took them out, I would clean the stalls, put fresh straw in each one. Then I got the bus into town for school. After school, I walked from home to the farm, and in the evening I milked the nanny goats. Sometimes I would carry a chicken home that Mr. Smythe had killed, I remember he killed it by slitting its throat from the inside and blood dripped from the sack I was carrying. It was food for the table.

One incident was the worst. We all had ration books that allowed us one-fourth pound of sweets a month if you could find it. I never saw candy. One day I was left alone to scrub from the front door down the hall, the kitchen, and the pantry. Well, I happened to look up and there was a bag of Peppermint Patties on the pantry shelf. I ate one—and ended up eating the whole bag, which I left in there. When Mrs. Smythe came home, she asked me what happened to it. “I ate it.” I never tell lies. She beat me with a stick. They had a long path going down to their back garden, where there was a big shed with no windows; I spent the night locked in that shed with thirteen cats. That was pretty horrible.

(No, nobody ever came to ask if I was being treated well, at least not that I knew of.) The little girl I slept with, Margie, would wet the bed, and I got the blame for it. Got to the point where I started sleepwalking, so traumatic. I should mention that I had a secret place that I went to every night when I went to bed; it was some kind of vehicle on runners like a sled. In my imagination, it was very dark and safe and I had books and blankets and I could go wherever I wanted and escape from the world.

Another incident: I was sent out to St. Austell to get fish & chips for supper. I had the money in my hands, got the fish & chips, and it was near where I went to school, so I could cut across the cemetery—maybe I was eleven at the time. An air-raid siren went off at the bottom of the cemetery and terrified me. The siren was mounted on the police station. I dropped the food, ran home with no food or money, and got a beating. To this day an air-raid siren puts the fear of God in me. [For an audio-clip:]

I had a little friend, Diana, a local girl. We used to go down and collect mussels. Had a little knife and you’d scrape them off rocks and put them into bags. I heard planes one day and knew they were German. I told Diana and she said “How do you know?” I told her to listen to the engines. “We’ve gotta go, we’ve gotta go!” I grabbed her by the hand and we ran and got under a row-boat. The planes strafed the beach while we hid.

I never remember a Christmas during the war. No presents. It was a work existence. And these people professed to be such Christians. We didn’t do work on Sunday—Sunday’s food was prepared on Saturday, except for food for the animals. Yes, I ate enough food. And I don’t ever remember being without clothes or shoes. They got a stipend from the government every month plus our ration books. The ration books were for clothing and meat. We had plenty of vegetables. Bread was mostly homemade, and there was a dairy down the street. Butter and margarine were hard to get; usually if we did manage to get real butter, we mixed it with margarine to make it go further You never threw the end of a bar of soap out but instead mashed it together [i.e., with other remainders].

My brother and sister had good homes. I had no real way to check on them in St. Austell.

The road to St. Austell went through forest. I had to walk there one evening and all of a sudden this man came out. It was the first dark-skinned man I had ever seen. He was from India, camping with his mule. (No, not a Gypsy: he was in the army.) Had a turban on. I was very scared and just ran off. In my little world I never knew much of what was going on till the end of the war.

One day I came home and a woman was standing right outside the front door. I recognized her as my mother, whom I had not seen for four-and-a-half years. Mrs. Smythe would not let her come in the house. Mother said, “You can get your things, we’re leaving.” Mrs. Smythe said, “You stay out here, she can get her things.”

My mother and father had divorced during those years and I only ever saw my dad once for about five minutes, standing in the street outside the house where we lived in Bristol [city in western England equidistant from London and St. Austell]. [Later asked by R.Wells if she had a photo of herself as a little girl, Norah reported that everything had been destroyed when her mother’s place had been “bombed out.”]

Thirty-two years later, I went back (sometime around 1977), after I had gotten a Christmas bonus of $1,000. My husband said, “Take it and go visit England.” I knew that I had go back to Charlestown. I knocked on the door and Mrs. Smythe answered. I said, “Do you know who I am?” “Yes, I do, you’re Norah.” “Well I want you to know that despite what you did to me I made it. I’m happy, I live in America with my husband and I have two lovely children.” “Uncle C. died”–that’s all she said. “Good-bye,” I said. It was good.

A lot of evacuees did well with their foster parents, but it was not the case for some of us.

I will admit that for many years I did carry a lot of resentment about those years but when I made my final visit and essentially “Closed The Door” on that part of my life, I realized that such adversity had made me a stronger person, better able to face the challenges that lay ahead.

….

This document belongs to Norah.

Copyright 2014 by Norah A. Mitchell, all rights reserved. Text, graphics and HTML code are protected by US & International Copyright Laws, and may not be copied, reprinted, published, translated, hosted or otherwise distributed by any means without explicit permission. Copyright transferred to Linda Motley, 2016, by Norah’s handwritten note.

Editor’s note. R. Wells has helped two other civilian casualties of World War II record their experiences and add these memoirs to the public record. Ernest G. Lion, b. 1915 in Germany, wrote The Fountain at the Crossroad (1999), an unpublished manuscript held by the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., and by Coastal Carolina University. The former Alzbeta Kačmarova–Elizabeth K. Pisanchik Moeringer–b. 1928 in Slovakia, spoke to an English class about surviving between German and Russian lines during 1944. A DVD recording of her talk and an edition of the transcript (by R. Wells) are housed at Coastal Carolina University. For vivid excerpts from the records of both Ernest and Elizabeth, see Angel in Goggles, the author’s ebook.